25 September 2025

As Spain and Italy send gunboats to protect the humanitarian flotilla bringing aid to Gaza, our waffle brothers continue to offer airy nothing in terms of action or meaningful sanctions. Shameful.

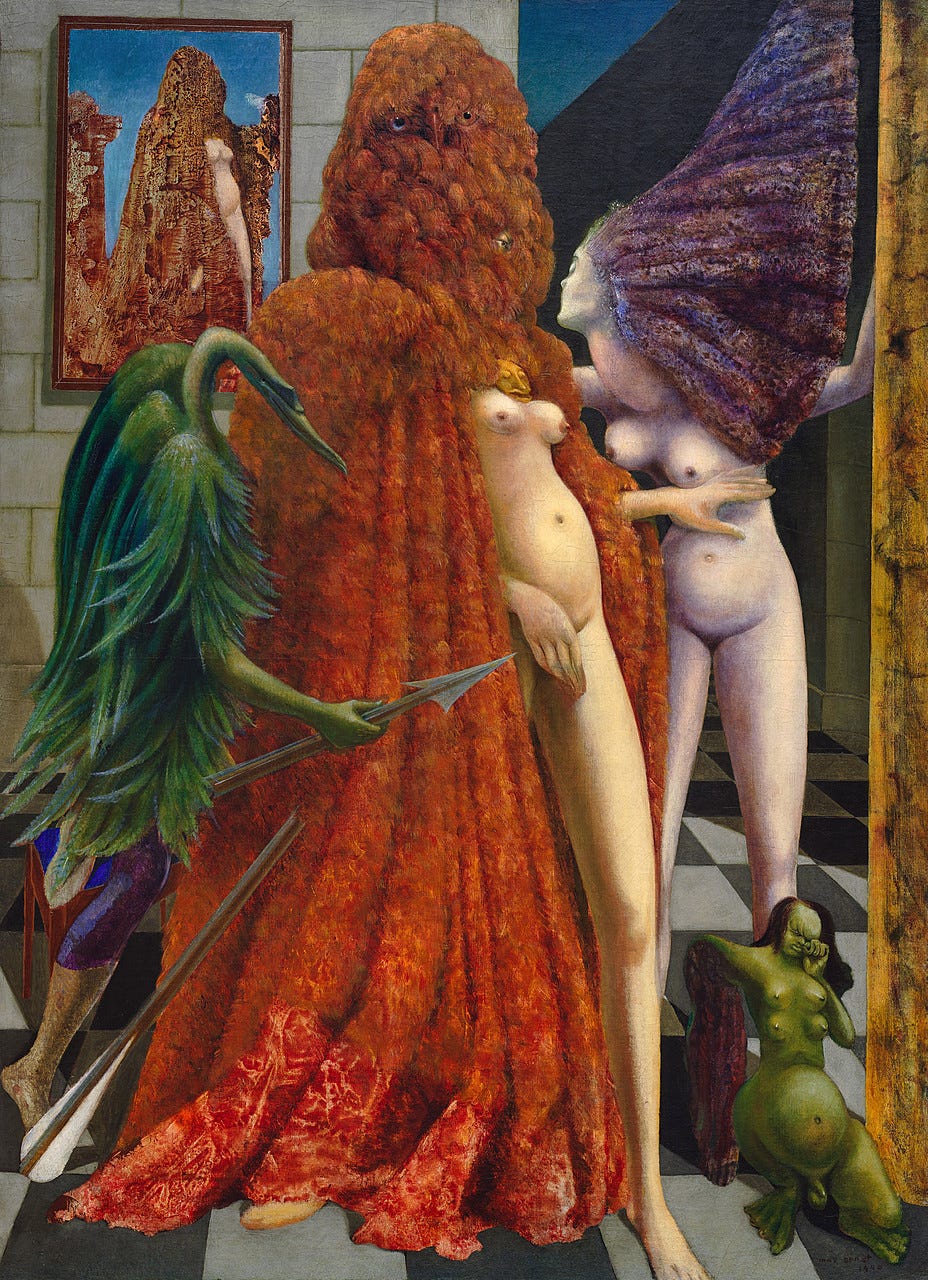

Picture of the Week

Just back from four days in Venice and currently reading the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington’s biography by Joanna Moorhead (see Bedtime Reading below). Hence this work by Max Ernst - The Attiring of the Bride, which I went to view at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection near Accademia. This famous piece is a surreal commentary on the relationship between Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim and the bould Leonora. Carrington, an adventurous and resourceful woman deserted Ernst for Renato Ducat, a Mexican diplomat, who facilitated her escape to the USA from the Nazis. Guggenheim swooped on the bereft Ernst (a hotel key discreetly passed after a dinner initiated the liaison). Thus began a relationship that worked out well materially for Ernst but left him much disgruntled as he considered Carrington the ‘love of his life”. The painting shows Carrington on the right with the peacock hair, her head averted. The orange-cloaked figure in the centre is Guggenheim (we hope the beak isn’t an unkind dig at Guggenheim’s much operated on nose) who owned a cloak of similar colour, and the sad bird-like figure with the broken lance is Loplop the Father Superior of birds - an alter ego of Ernst’s. This startling painting gets pride of place in Guggenheim’s museum and is one of Ernst’s finest works.

The Moronic Inferno

An extract from the dire warning posted by Robert Reich on Substack today :

“Actions now being taken by Trump and his regime may seem far-removed from your daily life or the lives of people you care about. But they’re not.

The U.S. military has attacked three boats in the Caribbean Sea suspected of smuggling drugs, killing at least 17 people.

Let me put this as directly as I can. The current occupant of the Oval Office is a thin-skinned sociopath who cannot tolerate criticism and who lies like most people breathe. Do you trust him with the power to murder anyone he says is transporting drugs to America?

It’s much the same with grabbing people from their homes who are legally in the United States and then whisking them off to prison because they’ve engaged in speech that Trump doesn’t like.

This is what happened to Mahmoud Khalil, who graduated from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs in December, who was in the United States legally on a green card as well as a student visa, and whose wife is an American citizen.

On March 8, immigration agents appeared at Khalil’s apartment building and told him he was being detained. They then revoked Khalil’s green card and student visa and held him at a Louisiana detention facility for 104 days before a federal judge ordered him released.

Khalil has never been charged with a crime. (In September, a Louisiana judge ordered him to be deported to either Syria or Algeria for allegedly failing to disclose information on his green card application. That decision is being appealed.)

Khalil was one of the leaders of last year’s peaceful pro-Palestinian protests at Columbia University. He expressed his political point of view nonviolently and non-threateningly. That’s supposed to be permitted — dare I say even encouraged? — in a democracy.

In a post on Truth Social, Trump conceded Khalil was snatched up and sent off because of his politics. “This is the first arrest of many to come,” Trump wrote. “We know there are more students at Columbia and other Universities across the Country who have engaged in pro-terrorist, anti-Semitic, anti-American activity, and the Trump Administration will not tolerate it.”

Nearly 13 million people in the United States hold green cards. Tens of thousands more are here temporarily as foreign students and professors. All are now in danger of being arrested if they speak their minds.

I am not blaming the ICE agents who are merely carrying out Trump’s “crackdown,” and there is absolutely no justification for political violence targeted at them or at anyone else.

My point is that, if you accept the legality of what is happening, nothing can stop Trump from arresting you or someone you care about for supporting any cause Trump doesn’t like — such as, say, replacing Republicans in Congress in 2026 and putting a Democrat in the White House in 2028.

I say this not to frighten you but to warn you of the implications of what is occurring.

It’s not just that Trump is nuts. It’s that he’s unilaterally acting as judge and jury in deciding who’s guilty of actions that are being punished with deportation, prison, or murder.

These moves personally and directly threaten the freedoms you and I take for granted. We must resist them. October 18 provides one opportunity (see here).”

You can read the rest on Substack. It’s free.

Musical Interlude

A song for our times. The riot squad are indeed restless as Trump’s masked goons roam the stinking ruins of the American empire and a Venezuelan with a random tattoo can be picked up while shopping and end up in jail in El Salvador or even the Congo.

Bedtime Reading

The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead. Reading this during my four-day break in Venice, I get a chance to view the art that was generated by Carrington’s devastating split with Max Ernst. Carrington was a beautiful, rebellious and adventurous woman. Her father was a wealthy English industrialist and her mother Marie (Moorhead) was Irish. Expelled from school she soon fled the strictures of home and found her way to art school and subsequently to bohemian company. Her life is some adventure: artist, novelist, proto-feminist, and friend of Picasso, Paul Eluard, Andre Breton, Duchamp and of course Ernst. She lived in Paris, the Ardeche, Madrid, New York and finally Mexico where she ended her days at the ripe old age of 94 - working to the very end. The author, a journalist with the Guardian and the Observer, has done a decent fact-finding job uncovering this eventful and fascinating life. Carrington was her father’s cousin, a fact Moorhead only discovered later in life - hence this book.

Sporting Highlights

If there were any, I missed them. But it would be churlish not to mention the eminently likeable Kate O’Connor’s silver medal in the Heptathlon at the World Championships. Our first medal in this event. Interesting to see that she has represented both Ireland and Northern Ireland in major championships. She was born in Newry.

Poetry Corner

This is just an extract from Hartnett’s poem - the whole lot can be found on The Inchicore Haiku blog run by Seoman - a resource new to me. It gives a flavour of Hartnett’s despondency during this phase of his life and his return to English after his dramatic farewell - albeit English using a Japanese format.

Inchicore Haiku by Michael Hartnett

1.

Now, in Inchicore

my cigarette-smoke rises-

like lonesome pub-talk.

2.

Down in Glendarragh

noises wake an anxious house.

I hear the doors slam.

3.

Dark sits here in me

and I leave all the lights on.

But nobody calls.

4.

Rain turns creator

and the dandelions explode

into supernovae.

5.

From daffodil cups

we drink Paddy-and-ginger -

the spring hangover.

6.

No goldfinches here -

puffed sparrows in sunpatches

like Dublin urchins.

7.

Stalking Emmet Road

a shocked rook blessed me with crusts -

manna for the dead.

8.

My English dam bursts

and out stroll all my bastards.

Irish shakes its head.

Artist’s Archive

John Behan is a significant figure in the history of 20th Century Irish art – not just for his bulls and Famine-themed sculpture, but also for the pioneering work he did in the 1960s to make the art world more democratic and for his establishment of a foundry where local artists could cast their bronzes without the expensive and tedious journeys to the UK. He emerged at a time when a coterie of middle-class figures including the architect Michael Scott, the gallery owner David Hendriks, the Arts Council autocrat Father Donal O’Sullivan, and their house critic Dorothy Walker ruled the scene and more significantly controlled the disbursements. Foreign influences and abstract art were cherished – social realism and working-class heroes were not encouraged.

When you meet him first you might expect a forceful and opinionated man as befits the rebel and a revolutionary he was. Instead, you encounter a gentle and soft-spoken person but one with a firm hold on his principles and beliefs. For a man-of-the-people I found he had excellent taste in wine – his preference lying with the whites, a Sancerre if possible but he wouldn’t turn his nose up at a Pouilly Fume. This interview was conducted at his home in Galway before his exhibition Seven Ages of Man at the Solomon Gallery in November 2018. This exhibition was inspired by his encounters with Syrian refugees in Greece for whom he conducted art workshops in Athens.

John Behan is 80 this year and still going strong. A major exhibition of new work by the Galway-based artist opened at the Solomon Gallery this week. It’s aptly entitled the Seven Ages of Man and this theme is explored in a series of seven bronze bulls. “I try to illustrate the bull’s journey through life” explains Behan. The show is not confined to his trademark bulls. It also contains work that depicts the plight of migrants from Syria. Behan travelled to Athens earlier this year (2018) to conduct workshops in the Eleonas refugee camp. He sees a connection between these displaced Syrians and those cast adrift by our Great Hunger (a recurring theme in his art). “What appeals to me is the parallel between their famine and our famine. They’re also on the sea and they’re vulnerable.”

Behan is now very much part of the art establishment. He’s a member of the RHA and Aosdána, and an honorary Doctor of Literature at NUI Galway. You will encounter his work in many public spaces around Ireland. Arrival, his giant bronze sculpture of a famine ship, stands outside the United Nations HQ in New York. However, he still retains that anger at injustice and the will to do something about it that made him such a revolutionary figure in the Irish art scene 50 years ago. I interviewed him in his quiet, canal-side house in the west of Galway city. Given his history as an agitator for fair play in the arts you’d expect an opinionated firebrand but instead you get a quietly-spoken, gentle man, his features still retaining a boyish quality. He moved to the west in 1980 to focus more on his art and get away from the art politics of Dublin in which he had been heavily embroiled. “I’d done my bit and I had to concentrate on my art.” Also, he had a connection with Kenny’s in Galway where he had exhibited occasionally. His marriage had broken up somewhat acrimoniously – so much so that a biography written a few years ago by Adrian Frazier did not mention his wife’s name – apparently at her request.

No one who is familiar with the development of the visual arts in Ireland over the last 50 years or more could quibble about Behan doing “his bit”. Behan is a truly seminal figure. He has had a major involvement in democratizing both the practice and the appreciation of the visual arts in this country. He fought against the attitude of people like David Hendricks who told him: “But you must realize that art is a snobbish business. It’s only for certain people.” Those with rougher edges and experimental urges were excluded from the polite worlds of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) and the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA). The Arts Council, where the writ of Fr. Donal O’Sullivan ruled, favored these organizations and socially acceptable practitioners such as Louis le Brocquy and Patrick Scott. In 1963 Behan set up the New Artists group with Charlie Cullen, Tadgh McSweeney, and Joseph O’Connor. They used to meet in O’Donoghue’s on Merrion Row. “We had this idea of art for the people.” This group morphed into the Independent Artists group that had been set up earlier by Noel Sheridan, Owen Walsh and Michael Kane. Behan accused the Arts Council of making funding decisions based on where artists came from. He had support from the press of the day. A headline over Anthony Butler’s article in the Evening Press proclaimed: “Artists call for the killing of the Arts Council” and Brian Fallon agreed that the Council’s buying policy appeared “arbitrary and exclusive to the point of to the point of cliquishness”. These young revolutionaries eventually got their way at the end of the 1960’s when Fine Gael returned to Government and overhauled the Arts Council, making Behan a member and giving a voice to those disaffected outsiders. He was also involved in the foundation of the Project Arts Centre with Colm O’Briain, another initiative towards democratizing the arts. He held the first exhibition, a set of lithographs, in the Project Gallery over a shop in Lower Abbey Street in 1967. He claims he was the first artist only “because nobody else had enough work ready.” An early indication of his formidable work ethic. Another signal achievement was the setting up of the Dublin Foundry with Leo Higgins with financial aid from Colm O’Briain’s father Peter. Prior to that, sculptors had to send their work to England to be cast, with all the attendant costs and logistical hassles. It was a labour of love for the artist. “I worked there for about 10 years for nothing. It was a hell of a struggle, we were working seven days a week.”

Behan’s background gave no clues to his future. He grew up in the industrial part of Sherrif Street where his father had a corner shop. Both his parents had farming backgrounds. His mother’s family were sheep farmers from Donegal (“lovely people, simple and direct”) and he recalls the musical influence of the famed Doherty family in the locale. His father was from “more substantial” farmers in Laois. He spent summers there helping out and had his first encounter with bulls. “They took our cow over to Hipwell’s bull to have it serviced.” Although he frequently acknowledges the influence of Thomas Kinsella’s translation of the Táin Bó Cúailnge on his art, these early rural experiences must have planted a seed.

Behan left an academic education behind at an early age. “I decided I’d had enough of the brothers at 11.” He enrolled at the North Strand Technical School to follow a more practical curriculum. He met a teacher there, Bill O’Brien, who presciently told him that “your temperament is more suited to the visual arts.” Behan remembers him warmly: “Bill was very enlightened, a lovely chap. He was the one who really got me going.” He left school at 15 to become an apprentice metal worker and continued his artistic studies by attending the National College of Art by night where he began to mix with artists such as Charlie Cullen and James McKenna. At 21 he made a decision to become a full-time sculptor. “I decided to retire from making gates and railings” - a very brave decision in late 50s Ireland. He went to London in 1960 for a year to work so he could fund his ambitions, and this proved to be an important finishing school for him. His visit coincided with a major Picasso exhibition that he describes as “the break-through exhibition for modern art in the English-speaking world.” He also discovered that “there was a big world out there of history, art and culture” of which he’d been unaware. “It woke me up to a completely different world.” His breakthrough as an artist came when he had a bronze bull accepted, ironically, by the IELA. He tells me how proud he was of the review in the Irish Times by James White who admired its “simple and witty conception.”

The current show is a tour de force. There’s something powerfully poignant about seeing that potent symbol of virility, the bull, go through the various stages from growth to disintegration. The works relating to the Syrian conflict may have a more immediate relevance for some. None more so than Alan Kurdi which captures in bronze that appalling image of a small boy being carried from the waters off the Turkish coast by a rescue worker. Elsewhere he highlights the parallels between our history and the current catastrophe in his juxtaposing of his familiar famine ships with the less substantial ribs associated with those fleeing Syria. Behan intends to return to Athens in the near future to continue his work with the Syrian migrants. He may have done his bit for Irish art but his zeal for supporting the underdog still endures.

John P. O’Sullivan

October 2018

Postscript:

John Behan is still going strong, and he has had a number of exhibitions since 2018. All of these exhibitions continue to highlight the plight of the hungry and the displaced – and to show the parallels between our Great Famine and those currently afflicted. His travels to Greece to conduct workshops for Syrian refugees was interrupted by Covid but his advocacy for the underdog is undimmed.

John P. O’Sullivan

25 September 2025

Inspiring, a masterful blend of art, culture and politics….